11 Spinning Compact Binaries

The post-Newtonian templates have been developed so far for compact binary systems which can be described with great precision by point masses without spins. Here by spin, we mean the intrinsic (classical) angular momentum of the individual compact body. However, including the effects of spins is essential,

as the astrophysical evidence indicates that stellar-mass black holes [2, 390, 311, 227, 323] and

supermassive black holes [188, 101, 102] (see Ref. [364] for a review) can be generically close to maximally

spinning. The presence of spins crucially affects the dynamics of the binary, in particular leading to

orbital plane precession if they are not aligned with the orbital angular momentum (see for

instance [138, 8]), and thereby to strong modulations in the observed signal frequency and

phase.

of the individual compact body. However, including the effects of spins is essential,

as the astrophysical evidence indicates that stellar-mass black holes [2, 390, 311, 227, 323] and

supermassive black holes [188, 101, 102] (see Ref. [364] for a review) can be generically close to maximally

spinning. The presence of spins crucially affects the dynamics of the binary, in particular leading to

orbital plane precession if they are not aligned with the orbital angular momentum (see for

instance [138, 8]), and thereby to strong modulations in the observed signal frequency and

phase.

In recent years an important effort has been undertaken to compute spin effects to high post-Newtonian order in the dynamics and gravitational radiation of compact binaries:

- Dynamics. The goal is to obtain the equations of motion and related conserved integrals of the motion, the equations of precession of the spins, and the post-Newtonian metric in the near zone. For this step we need a formulation of the dynamics of particles with spins (either Lagrangian or Hamiltonian);

- Radiation. The mass and current radiative multipole moments, including tails and all hereditary effects, are to be computed. One then deduces the gravitational waveform and the fluxes, from which we compute the secular evolution of the orbital phase. This step requires plugging the previous dynamics into the general wave generation formalism of Part A.

We adopt a particular post-Newtonian counting for spin effects that actually refers to maximally

spinning black holes. In this convention the two spin variables  have the dimension of an

angular momentum multiplied by a factor

have the dimension of an

angular momentum multiplied by a factor  , and we pose

, and we pose

is the mass of the compact body, and

is the mass of the compact body, and  is the dimensionless spin parameter, which equals

one for maximally spinning Kerr black holes. Thus the spins

is the dimensionless spin parameter, which equals

one for maximally spinning Kerr black holes. Thus the spins  of the compact bodies can be considered

as “Newtonian” quantities [there are no

of the compact bodies can be considered

as “Newtonian” quantities [there are no  ’s in Eq. (366*)], and all spin effects will carry (at least) an

explicit

’s in Eq. (366*)], and all spin effects will carry (at least) an

explicit  factor with respect to non-spin effects. With this convention any post-Newtonian estimate is

expected to be appropriate (i.e., numerically correct) in the case of maximal rotation. One should keep in

mind that spin effects will be formally a factor

factor with respect to non-spin effects. With this convention any post-Newtonian estimate is

expected to be appropriate (i.e., numerically correct) in the case of maximal rotation. One should keep in

mind that spin effects will be formally a factor  smaller for non-maximally spinning objects such as

neutron stars; thus in this case a given post-Newtonian computation will actually be a factor

smaller for non-maximally spinning objects such as

neutron stars; thus in this case a given post-Newtonian computation will actually be a factor  more

accurate.

more

accurate.

As usual we shall make a distinction between spin-orbit (SO) effects, which are linear in the spins, and spin-spin (SS) ones, which are quadratic. In this article we shall especially review the SO effects as they play the most important role in gravitational wave detection and parameter estimation. As we shall see a good deal is known on spin effects (both SO and SS), but still it will be important in the future to further improve our knowledge of the waveform and gravitational-wave phasing, by computing still higher post-Newtonian SO and SS terms, and to include at least the dominant spin-spin-spin (SSS) effect [305*]. For the computations of SSS and even SSSS effects see Refs. [246, 245, 296, 305, 413].

The SO effects have been known at the leading level since the seminal works of Tulczyjew [411*, 412*], Barker & O’Connell [27*, 28*] and Kidder et al. [275*, 271*]. With our post-Newtonian counting such leading level corresponds to the 1.5PN order. The SO terms have been computed to the next-to-leading level which corresponds to 2.5PN order in Refs. [394*, 194*, 165*, 292*, 352*, 241*] for the equations of motion or dynamics, and in Refs. [53*, 54*] for the gravitational radiation field. Note that Refs. [394, 194, 165*, 241*] employ traditional post-Newtonian methods (both harmonic-coordinates and Hamiltonian), but that Refs. [292, 352] are based on the effective field theory (EFT) approach. The next-to-next-to-leading SO level corresponding to 3.5PN order has been obtained in Refs. [242, 244] using the Hamiltonian method for the equations of motion, in Ref. [297] using the EFT, and in Refs. [307*, 90*] using the harmonic-coordinates method. Here we shall focus on the harmonic-coordinates approach [307*, 90*, 89*, 306*] which is in fact best formulated using a Lagrangian, see Section 11.1. With this approach the next-to-next-to-leading SO level was derived not only for the equations of motion including precession, but also for the radiation field (energy flux and orbital phasing) [89*, 306*]. An analytic solution for the SO precession effects will be presented in Section 11.2. Note that concerning the radiation field the highest known SO level actually contains specific tail-induced contributions at 3PN [54*] and 4PN [306*] orders, see Section 11.3.

The SS effects are known at the leading level corresponding to 2PN order from Barker &

O’Connell [27, 28] in the equations of motion (see [271*, 351*, 110] for subsequent derivations), and from

Refs. [275, 271*] in the radiation field. Next-to-leading SS contributions are at 3PN order and have been

obtained with Hamiltonian [387, 389*, 388, 247, 241], EFT [354, 356, 355, 293, 299] and

harmonic-coordinates [88*] techniques (with [88] obtaining also the next-to-leading SS terms in the

gravitational-wave flux). With SS effects in a compact binary system one must make a distinction between

the spin squared terms, involving the coupling between the two same spins  or

or  , and the interaction

terms, involving the coupling between the two different spins

, and the interaction

terms, involving the coupling between the two different spins  and

and  . The spin-squared terms

. The spin-squared terms  and

and  arise due to the effects on the dynamics of the quadrupole moments of the compact

bodies that are induced by their spins [347]. They have been computed through 2PN order in

the fluxes and orbital phase in Refs. [217, 218*, 314]. The interaction terms

arise due to the effects on the dynamics of the quadrupole moments of the compact

bodies that are induced by their spins [347]. They have been computed through 2PN order in

the fluxes and orbital phase in Refs. [217, 218*, 314]. The interaction terms  can be

computed using a simple pole-dipole formalism like the one we shall review in Section 11.1. The

interaction terms

can be

computed using a simple pole-dipole formalism like the one we shall review in Section 11.1. The

interaction terms  between different spins have been derived to next-to-next-to-leading

4PN order for the equations of motion in Refs. [294, 298] (EFT) and [243] (Hamiltonian). In

this article we shall generally neglect the SS effects and refer for these to the literature quoted

above.

between different spins have been derived to next-to-next-to-leading

4PN order for the equations of motion in Refs. [294, 298] (EFT) and [243] (Hamiltonian). In

this article we shall generally neglect the SS effects and refer for these to the literature quoted

above.

11.1 Lagrangian formalism for spinning point particles

Some necessary material for constructing a Lagrangian for a spinning point particle in curved spacetime is presented here. The formalism is issued from early works [239*, 19*] and has also been developed in the context of the EFT approach [351*]. Variants and alternatives (most importantly the associated Hamiltonian formalism) can be found in Refs. [389, 386, 25]. The formalism yields for the equations of motion of spinning particles and the equations of precession of the spins the classic results known in general relativity [411*, 412*, 310*, 331*, 135*, 409*, 179*].

Let us consider a single spinning point particle moving in a given curved background metric

. The particle follows the worldline

. The particle follows the worldline  , with tangent four-velocity

, with tangent four-velocity  ,

where

,

where  is a parameter along the representative worldline. In a first stage we do not require

that the four-velocity be normalized; thus

is a parameter along the representative worldline. In a first stage we do not require

that the four-velocity be normalized; thus  needs not be the proper time elapsed along the

worldline. To describe the internal degrees of freedom associated with the particle’s spin, we

introduce a moving orthonormal tetrad

needs not be the proper time elapsed along the

worldline. To describe the internal degrees of freedom associated with the particle’s spin, we

introduce a moving orthonormal tetrad  along the trajectory, which defines a “body-fixed”

frame.77

The rotation tensor

along the trajectory, which defines a “body-fixed”

frame.77

The rotation tensor  associated with the tetrad is defined by

associated with the tetrad is defined by

is the covariant derivative with respect to the parameter

is the covariant derivative with respect to the parameter  along the worldline;

equivalently, we have

Because of the normalization of the tetrad the rotation tensor is antisymmetric:

along the worldline;

equivalently, we have

Because of the normalization of the tetrad the rotation tensor is antisymmetric:  .

.

We look for an action principle for the spinning particle. Following Refs. [239*, 351] and the general spirit of effective field theories, we require the following symmetries to hold:

- The action is a covariant scalar, i.e., behaves as a scalar with respect to general space-time diffeomorphisms;

- It is a global Lorentz scalar, i.e., stays invariant under an arbitrary change of the tetrad vectors:

where

where  is a constant Lorentz matrix;

is a constant Lorentz matrix;

- It is reparametrization-invariant, i.e., its form is independent of the parameter

used to

follow the particle’s worldline.

used to

follow the particle’s worldline.

In addition to these symmetries we need to specify the dynamical degrees of freedom: These are chosen to be

the particle’s position  and the tetrad

and the tetrad  . Furthermore we restrict ourselves to a Lagrangian

depending only on the four-velocity

. Furthermore we restrict ourselves to a Lagrangian

depending only on the four-velocity  , the rotation tensor

, the rotation tensor  , and the metric

, and the metric  . Thus, the

postulated action is of the type

. Thus, the

postulated action is of the type

As it is written in (369*), i.e., depending only on Lorentz scalars,  is automatically a Lorentz scalar.

By performing an infinitesimal coordinate transformation, one easily sees that the requirement that the

Lagrangian be a covariant scalar specifies its dependence on the metric to be such that (see e.g., Ref. [19])

is automatically a Lorentz scalar.

By performing an infinitesimal coordinate transformation, one easily sees that the requirement that the

Lagrangian be a covariant scalar specifies its dependence on the metric to be such that (see e.g., Ref. [19])

and the antisymmetric spin tensor

and the antisymmetric spin tensor  by

by

Note that the right-hand side of Eq. (370*) is necessarily symmetric by exchange of the indices  and

and

. Finally, imposing the invariance of the action (369*) by reparametrization of the worldline, we find

that the Lagrangian must be a homogeneous function of degree one in the velocity

. Finally, imposing the invariance of the action (369*) by reparametrization of the worldline, we find

that the Lagrangian must be a homogeneous function of degree one in the velocity  and

rotation tensor

and

rotation tensor  . Applying Euler’s theorem to the function

. Applying Euler’s theorem to the function  immediately gives

immediately gives

and

and  must be reparametrization invariant. Note that, at this

stage, their explicit expressions are not known. They will be specified only when a spin supplementary

condition is imposed, see Eq. (379*) below.

must be reparametrization invariant. Note that, at this

stage, their explicit expressions are not known. They will be specified only when a spin supplementary

condition is imposed, see Eq. (379*) below.

We now investigate the unconstrained variations of the action (369*) with respect to the dynamical

variables  ,

,  and the metric. First, we vary it with respect to the tetrad

and the metric. First, we vary it with respect to the tetrad  while keeping the

position

while keeping the

position  fixed. A worry is that we must have a way to distinguish intrinsic variations of the tetrad

from variations which are induced by a change of the metric

fixed. A worry is that we must have a way to distinguish intrinsic variations of the tetrad

from variations which are induced by a change of the metric  . This is conveniently solved by

decomposing the variation

. This is conveniently solved by

decomposing the variation  according to

according to

![αβ A [α β] δ𝜃 ≡ e δeA](article2856x.gif) , and where the corresponding

symmetric part is simply given by the variation of the metric, i.e.

, and where the corresponding

symmetric part is simply given by the variation of the metric, i.e.  . Then we can

consider the independent variations

. Then we can

consider the independent variations  and

and  . Varying with respect to

. Varying with respect to  , but holding the

metric fixed, gives the equation of spin precession which is found to be

or, alternatively, using the fact that the right-hand side of Eq. (370*) is symmetric,

We next vary with respect to the particle’s position

, but holding the

metric fixed, gives the equation of spin precession which is found to be

or, alternatively, using the fact that the right-hand side of Eq. (370*) is symmetric,

We next vary with respect to the particle’s position  while holding the tetrad

while holding the tetrad  fixed.

Operationally, this means that we have to parallel-transport the tetrad along the displacement vector, i.e.,

to impose

A simple way to derive the result is to use locally inertial coordinates, such that the Christoffel symbols

fixed.

Operationally, this means that we have to parallel-transport the tetrad along the displacement vector, i.e.,

to impose

A simple way to derive the result is to use locally inertial coordinates, such that the Christoffel symbols

along the particle’s worldline

along the particle’s worldline  ; then, Eq. (376*) gives

; then, Eq. (376*) gives  .

The variation leads then to the well-known Mathisson–Papapetrou [310*, 331*, 135*] equation of motion

which involves the famous coupling of the spin tensor to the Riemann

curvature.78

With a little more work, the equation of motion (377*) can also be derived using an arbitrary coordinate

system, making use of the parallel transport equation (376*). Finally, varying with respect to the metric

while keeping

.

The variation leads then to the well-known Mathisson–Papapetrou [310*, 331*, 135*] equation of motion

which involves the famous coupling of the spin tensor to the Riemann

curvature.78

With a little more work, the equation of motion (377*) can also be derived using an arbitrary coordinate

system, making use of the parallel transport equation (376*). Finally, varying with respect to the metric

while keeping  , gives the stress-energy tensor of the spinning particle. We must again take into

account the scalarity of the action, as imposed by Eq. (370*). We obtain the standard pole-dipole

result [411*, 412*, 310, 331, 135, 409, 179]:

where

, gives the stress-energy tensor of the spinning particle. We must again take into

account the scalarity of the action, as imposed by Eq. (370*). We obtain the standard pole-dipole

result [411*, 412*, 310, 331, 135, 409, 179]:

where  denotes the four-dimensional Dirac function. It can easily be checked that the covariant

conservation law

denotes the four-dimensional Dirac function. It can easily be checked that the covariant

conservation law  holds as a consequence of the equation of motion (377*) and the equation of

spin precession (375*).

holds as a consequence of the equation of motion (377*) and the equation of

spin precession (375*).

Up to now we have considered unconstrained variations of the action (369*), describing the particle’s

internal degrees of freedom by the six independent components of the tetrad  (namely a

(namely a  matrix subject to the 10 constraints

matrix subject to the 10 constraints  ). To correctly account for the number of degrees of

freedom associated with the spin, we must impose three supplementary spin conditions (SSC). Several

choices are possible for a sensible SSC. Notice that in the case of extended bodies the choice of a SSC

corresponds to the choice of a central worldline inside the body with respect to which the spin angular

momentum is defined (see Ref. [271*] for a discussion). Here we adopt the Tulczyjew covariant

SSC [411, 412]

). To correctly account for the number of degrees of

freedom associated with the spin, we must impose three supplementary spin conditions (SSC). Several

choices are possible for a sensible SSC. Notice that in the case of extended bodies the choice of a SSC

corresponds to the choice of a central worldline inside the body with respect to which the spin angular

momentum is defined (see Ref. [271*] for a discussion). Here we adopt the Tulczyjew covariant

SSC [411, 412]

associated with the spin tensor

by79

where we have defined the mass of the particle by

associated with the spin tensor

by79

where we have defined the mass of the particle by  . By contracting Eq. (375*) with

. By contracting Eq. (375*) with  and using the equation of motion (377*), one obtains

where we denote

and using the equation of motion (377*), one obtains

where we denote  . By further contracting Eq. (381*) with

. By further contracting Eq. (381*) with  we obtain an explicit

expression for

we obtain an explicit

expression for  , which can then be substituted back into (381*) to provide the relation linking the

four-momentum

, which can then be substituted back into (381*) to provide the relation linking the

four-momentum  to the four-velocity

to the four-velocity  . It can be checked using (379*) and (381*) that the

mass of the particle is constant along the particle’s trajectory:

. It can be checked using (379*) and (381*) that the

mass of the particle is constant along the particle’s trajectory:  . Furthermore

the four-dimensional magnitude

. Furthermore

the four-dimensional magnitude  of the spin defined by

of the spin defined by  is also conserved:

is also conserved:

.

.

Henceforth we shall restrict our attention to spin-orbit (SO) interactions, which are linear in

the spins. We shall also adopt for the parameter  along the particle’s worldline the proper

time

along the particle’s worldline the proper

time  , so that

, so that  . Neglecting quadratic spin-spin (SS) and

higher-order interactions, the linear momentum is simply proportional to the normalized four-velocity:

. Neglecting quadratic spin-spin (SS) and

higher-order interactions, the linear momentum is simply proportional to the normalized four-velocity:

. Hence, from Eq. (375*) we deduce that

. Hence, from Eq. (375*) we deduce that  . The equation for the

spin covariant vector

. The equation for the

spin covariant vector  then reduces at linear order to

then reduces at linear order to

remainders.

remainders.

In applications (e.g., the construction of gravitational wave templates for the compact binary inspiral) it

is very useful to introduce new spin variables that are designed to have a conserved three-dimensional

Euclidean norm (numerically equal to  ). Using conserved-norm spin vector variables is indeed the most

natural choice when considering the dynamics of compact binaries reduced to the frame of the center of

mass or to circular orbits [90*]. Indeed the evolution equations of such spin variables reduces, by

construction, to ordinary precession equations, and these variables are secularly constant (see

Ref. [423*]).

). Using conserved-norm spin vector variables is indeed the most

natural choice when considering the dynamics of compact binaries reduced to the frame of the center of

mass or to circular orbits [90*]. Indeed the evolution equations of such spin variables reduces, by

construction, to ordinary precession equations, and these variables are secularly constant (see

Ref. [423*]).

A standard, general procedure to define a (Euclidean) conserved-norm spin spatial vector consists of

projecting the spin covector  onto an orthonormal tetrad

onto an orthonormal tetrad  , which leads to the four scalar

components (

, which leads to the four scalar

components ( )

)

,80

the time component tetrad projection

,80

the time component tetrad projection  vanishes because of the orthogonality condition (383*). We have

seen that

vanishes because of the orthogonality condition (383*). We have

seen that  is conserved along the trajectory; because of (383*) we can rewrite this as

is conserved along the trajectory; because of (383*) we can rewrite this as

, in which we have introduced the projector

, in which we have introduced the projector  onto the spatial

hypersurface orthogonal to

onto the spatial

hypersurface orthogonal to  . From the orthonormality of the tetrad and our choice

. From the orthonormality of the tetrad and our choice  , we

have

, we

have  in which

in which  refer to the spatial values of the tetrad indices,

i.e.,

refer to the spatial values of the tetrad indices,

i.e.,  and

and  . Therefore the conservation law

. Therefore the conservation law  becomes

which is indeed the relation defining a Euclidean conserved-norm spin variable

becomes

which is indeed the relation defining a Euclidean conserved-norm spin variable

.81

However, note that the choice of the spin variable

.81

However, note that the choice of the spin variable  is still somewhat arbitrary, since a rotation of

the tetrad vectors can freely be performed. We refer to [165, 90*] for the definition of some

“canonical” choice for the tetrad in order to fix this residual freedom. Such choice presents

the advantage of providing a unique determination of the conserved-norm spin variable in a

given gauge. This canonical choice will be the one adopted in all explicit results presented in

Section 11.3.

is still somewhat arbitrary, since a rotation of

the tetrad vectors can freely be performed. We refer to [165, 90*] for the definition of some

“canonical” choice for the tetrad in order to fix this residual freedom. Such choice presents

the advantage of providing a unique determination of the conserved-norm spin variable in a

given gauge. This canonical choice will be the one adopted in all explicit results presented in

Section 11.3.

The evolution equation (382*) for the original spin variable  now translates into an ordinary

precession equation for the tetrad components

now translates into an ordinary

precession equation for the tetrad components  , namely

, namely

is related to the tetrad components

is related to the tetrad components  of the rotation tensor defined

in (368*) by

of the rotation tensor defined

in (368*) by  where we pose

where we pose  , remembering the redshift variable (276*). The

antisymmetric character of the matrix

, remembering the redshift variable (276*). The

antisymmetric character of the matrix  guaranties that

guaranties that  satisfies the Euclidean precession

equation

where we denote

satisfies the Euclidean precession

equation

where we denote  , and

, and  with

with  . As a consequence of (387*) the spin

has a conserved Euclidean norm:

. As a consequence of (387*) the spin

has a conserved Euclidean norm:  . From now on we shall no longer make any distinction between

the spatial tetrad indices

. From now on we shall no longer make any distinction between

the spatial tetrad indices  and the ordinary spatial indices

and the ordinary spatial indices  which are raised and lowered with

the Kronecker metric. Explicit results for the equations of motion and gravitational wave templates will be

given in Sections 11.2 and 11.3 using the canonical choice for the conserved-norm spin variable

which are raised and lowered with

the Kronecker metric. Explicit results for the equations of motion and gravitational wave templates will be

given in Sections 11.2 and 11.3 using the canonical choice for the conserved-norm spin variable

.

.

11.2 Equations of motion and precession for spin-orbit effects

The previous formalism can be generalized to self-gravitating systems consisting of two (or more generally N) spinning point particles. The metric generated by the system of particles, interacting only through gravitation, is solution of the Einstein field equations (18*) with stress-energy tensor given by the sum of the individual stress-energy tensors (378*) for each particles. The equations of motion of the particles are given by the Mathisson–Papapetrou equations (377*) with “self-gravitating” metric evaluated at the location of the particles thanks to a regularization procedure (see Section 6). The precession equations of each of the spins are given by

where labels the particles. The spin variables

labels the particles. The spin variables  are the conserved-norm spins defined in Section 11.1. In

the following it is convenient to introduce two combinations of the individuals spins defined by (with

are the conserved-norm spins defined in Section 11.1. In

the following it is convenient to introduce two combinations of the individuals spins defined by (with  and

and

)82

)82

We shall investigate the case where the binary’s orbit is quasi-circular, i.e., whose radius is constant

apart from small perturbations induced by the spins (as usual we neglect the gravitational

radiation damping effects). We denote by  and

and  the relative position and

velocity.83

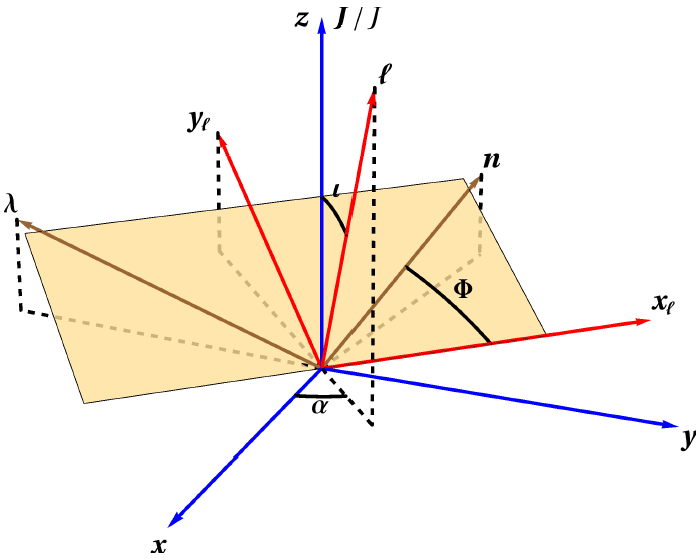

We introduce an orthonormal moving triad

the relative position and

velocity.83

We introduce an orthonormal moving triad  defined by the unit separation vector

defined by the unit separation vector  (with

(with  ) and the unit normal

) and the unit normal  to the instantaneous orbital plane given by

to the instantaneous orbital plane given by  ;

the orthonormal triad is then completed by

;

the orthonormal triad is then completed by  . Those vectors are represented on Figure 4*, which

shows the geometry of the system. The orbital frequency

. Those vectors are represented on Figure 4*, which

shows the geometry of the system. The orbital frequency  is defined for general orbits, not necessarily

circular, by

is defined for general orbits, not necessarily

circular, by  where

where  represents the derivative of

represents the derivative of  with respect to the

coordinate time

with respect to the

coordinate time  . The general expression for the relative acceleration

. The general expression for the relative acceleration  decomposed in the

moving basis

decomposed in the

moving basis  is

is

of the orbit defined by

of the orbit defined by  . Next

we impose the restriction to quasi-circular precessing orbits which is defined by the conditions

. Next

we impose the restriction to quasi-circular precessing orbits which is defined by the conditions

and

and  so that

so that  ; see Eqs. (227). Then

; see Eqs. (227). Then  represents the direction of the velocity, and the precession frequency

represents the direction of the velocity, and the precession frequency  is proportional to the variation of

is proportional to the variation of

in the direction of the velocity. In this way we find that the equations of the relative motion in the

frame of the center-of-mass are

Since we neglect the radiation reaction damping there is no component of the acceleration along

in the direction of the velocity. In this way we find that the equations of the relative motion in the

frame of the center-of-mass are

Since we neglect the radiation reaction damping there is no component of the acceleration along  . This

equation represents the generalization of Eq. (226*) for spinning quasi-circular binaries with

no radiation reaction. The orbital frequency

. This

equation represents the generalization of Eq. (226*) for spinning quasi-circular binaries with

no radiation reaction. The orbital frequency  will contain spin effects in addition to the

non-spin terms given by (228), while the precessional frequency

will contain spin effects in addition to the

non-spin terms given by (228), while the precessional frequency  will entirely be due to

spins.

will entirely be due to

spins.

Here we report the latest results for the spin-orbit (SO) contributions into these quantities at the

next-to-next-to-leading level corresponding to 3.5PN order [307*, 90*]. We project out the spins on

the moving orthonormal basis, defining  and similarly for

and similarly for  . We

have

. We

have

which has to be added to the non-spin terms (228) up to 3.5PN order. We recall that the ordering

post-Newtonian parameter is  . On the other hand the next-to-next-to-leading SO effects into the

precessional frequency read

. On the other hand the next-to-next-to-leading SO effects into the

precessional frequency read

where this time the ordering post-Newtonian parameter is  . The SO terms at the

same level in the conserved energy associated with the equations of motion will be given in

Eq. (415) below. In order to complete the evolution equations for quasi-circular orbits we need

also the precession vectors

. The SO terms at the

same level in the conserved energy associated with the equations of motion will be given in

Eq. (415) below. In order to complete the evolution equations for quasi-circular orbits we need

also the precession vectors  of the two spins as defined by Eq. (388*). These are given

by

of the two spins as defined by Eq. (388*). These are given

by

We obtain  from

from  simply by exchanging the masses,

simply by exchanging the masses,  .

At the linear SO level the precession vectors

.

At the linear SO level the precession vectors  are independent of the

spins.84

are independent of the

spins.84

We now investigate an analytical solution for the dynamics of compact spinning binaries on quasi-circular orbits, including the effects of spin precession [54*, 306*]. This solution will be valid whenever the radiation reaction effects can be neglected, and is restricted to the linear SO level.

; (ii) the instantaneous

orbital plane which is described by the orthonormal basis

; (ii) the instantaneous

orbital plane which is described by the orthonormal basis  ; (iii) the moving triad

; (iii) the moving triad

and the associated three Euler angles

and the associated three Euler angles  ,

,  and

and  ; (v) the direction of the total

angular momentum

; (v) the direction of the total

angular momentum  which coincides with the

which coincides with the  –direction. Dashed lines show projections into

the

–direction. Dashed lines show projections into

the  –

– plane.

plane. In the following, we will extensively employ the total angular momentum of the system,

that we denote by  , and which is conserved when radiation-reaction effects are neglected,

, and which is conserved when radiation-reaction effects are neglected,

as the sum of the orbital angular momentum

as the sum of the orbital angular momentum  and

of the two spins,85

This split between

and

of the two spins,85

This split between  and

and  is specified by our choice of spin variables, here the

conserved-norm spins defined in Section 11.1. Note that although

is specified by our choice of spin variables, here the

conserved-norm spins defined in Section 11.1. Note that although  is called the “orbital”

angular momentum, it actually includes both non-spin and spin contributions. We refer to

Eq. (4.7) in [90*] for the expression of

is called the “orbital”

angular momentum, it actually includes both non-spin and spin contributions. We refer to

Eq. (4.7) in [90*] for the expression of  at the next-to-next-to-leading SO level for quasi-circular

orbits.

at the next-to-next-to-leading SO level for quasi-circular

orbits.

Our solution will consist of some explicit expressions for the moving triad  at the SO level in

the conservative dynamics for quasi-circular orbits. With the previous definitions of the orbital frequency

at the SO level in

the conservative dynamics for quasi-circular orbits. With the previous definitions of the orbital frequency

and the precessional frequency

and the precessional frequency  we have the following system of equations for the time evolution of

the triad vectors,

we have the following system of equations for the time evolution of

the triad vectors,

Equivalently, introducing the orbital rotation vector  and spin precession vector

and spin precession vector  ,

these equations can be elegantly written as

,

these equations can be elegantly written as

Next we introduce a fixed (inertial) orthonormal basis  as follows:

as follows:  is defined to be the

normalized value

is defined to be the

normalized value  of the total angular momentum

of the total angular momentum  ;

;  is orthogonal to the plane spanned by

is orthogonal to the plane spanned by  and the direction

and the direction  of the detector as seen from the source (notation of Section 3.1) and is

defined by

of the detector as seen from the source (notation of Section 3.1) and is

defined by  ; and

; and  completes the triad – see Figure 4*. Then, we introduce

the standard spherical coordinates

completes the triad – see Figure 4*. Then, we introduce

the standard spherical coordinates  of the vector

of the vector  measured in the inertial basis

measured in the inertial basis

. Since

. Since  is the angle between the total and orbital angular momenta, we have

is the angle between the total and orbital angular momenta, we have

. The angles

. The angles  are referred to as the precession angles.

are referred to as the precession angles.

We now derive from the time evolution of our triad vectors those of the precession angles  , and of

an appropriate phase

, and of

an appropriate phase  that specifies the position of

that specifies the position of  with respect to some reference direction in the

orbital plane denoted

with respect to some reference direction in the

orbital plane denoted  . Following Ref. [13], we pose

. Following Ref. [13], we pose

such that  forms an orthonormal basis. The motion takes place in the instantaneous

orbital plane spanned by

forms an orthonormal basis. The motion takes place in the instantaneous

orbital plane spanned by  and

and  , and the phase angle

, and the phase angle  is such that (see Figure 4*):

is such that (see Figure 4*):

from which we deduce

Combining Eqs. (402*) with (399*) we also get By identifying the right-hand sides of (397) with the time-derivatives of the relations (401) we obtain the following system of equations for the variations of ,

,  and

and  ,

,

On the other hand, using the decompositon of the total angular momentum (396*) together with the fact

that the components of  projected along

projected along  and

and  are of the order

are of the order  , see e.g., Eq. (4.7) in

Ref. [90*], we deduce that

, see e.g., Eq. (4.7) in

Ref. [90*], we deduce that  is itself a small quantity of order

is itself a small quantity of order  . Since we also have

. Since we also have

, we conclude by direct integration of the sum of Eqs. (404a) and (404c) that

, we conclude by direct integration of the sum of Eqs. (404a) and (404c) that

the value of the carrier phase at some arbitrary initial time

the value of the carrier phase at some arbitrary initial time  . An important point we have

used when integrating (406*) is that the orbital frequency

. An important point we have

used when integrating (406*) is that the orbital frequency  is constant at linear order in the

spins. Indeed, from Eq. (392) we see that only the components of the conserved-norm spin

vectors along

is constant at linear order in the

spins. Indeed, from Eq. (392) we see that only the components of the conserved-norm spin

vectors along  can contribute to

can contribute to  at linear order. As we show in Eq. (409c) below, these

components are in fact constant at linear order in spins. Thus we can treat

at linear order. As we show in Eq. (409c) below, these

components are in fact constant at linear order in spins. Thus we can treat  as a constant for our

purpose.

as a constant for our

purpose.

The combination  being known by Eq. (405*), we can further express the precession angles

being known by Eq. (405*), we can further express the precession angles  and

and  at linear order in spins in terms of the components

at linear order in spins in terms of the components  and

and  ; from Eqs. (399*) and (403*):

; from Eqs. (399*) and (403*):

where we denote by  the norm of the non-spin (NS) part of the orbital angular momentum

the norm of the non-spin (NS) part of the orbital angular momentum

.

.

It remains to obtain the explicit time variation of the components of the two individual spins  ,

,

and

and  (with

(with  ). Using Eqs. (407) together with the decomposition (396*) and

the explicit expression of

). Using Eqs. (407) together with the decomposition (396*) and

the explicit expression of  in Ref. [90*], we shall then be able to obtain the explicit time

variation of the precession angles

in Ref. [90*], we shall then be able to obtain the explicit time

variation of the precession angles  and phase

and phase  . Combining (388*) and (397) we obtain

. Combining (388*) and (397) we obtain

where  is the norm of the precession vector of the

is the norm of the precession vector of the  -th spin as given by (394), and the precession

frequency

-th spin as given by (394), and the precession

frequency  is explicitly given by (393). At linear order in spins these equations translate into

is explicitly given by (393). At linear order in spins these equations translate into

We see that, as stated before, the spin components along  are constant, and so is the orbital

frequency

are constant, and so is the orbital

frequency  given by (392). At the linear SO level, the equations (409) can be decoupled and integrated

as

given by (392). At the linear SO level, the equations (409) can be decoupled and integrated

as

Here  and

and  denote two quantities for each spins, that are constant up to terms

denote two quantities for each spins, that are constant up to terms  .

The phase of the projection perpendicular to the direction

.

The phase of the projection perpendicular to the direction  of each of the spins is given by

of each of the spins is given by

is the constant initial phase at the reference time

is the constant initial phase at the reference time  .

.

Finally we can give in an explicit way, to linear SO order, the triad  in terms of

some reference triad

in terms of

some reference triad  at the reference time

at the reference time  in Eqs. (411*) and (406*). The

best way to express the result is to introduce the complex null vector

in Eqs. (411*) and (406*). The

best way to express the result is to introduce the complex null vector  and

its complex conjuguate

and

its complex conjuguate  ; the normalization is chosen so that

; the normalization is chosen so that  . We obtain

. We obtain

The precession effects in the dynamical solution for the evolution of the basis vectors  are

given by the second terms in these equations. They depend only in the combination

are

given by the second terms in these equations. They depend only in the combination  and its

complex conjugate

and its

complex conjugate  , which follows from Eqs. (407) and the known spin and non-spin

contributions to the total angular momentum

, which follows from Eqs. (407) and the known spin and non-spin

contributions to the total angular momentum  . One can check that precession effects in the above

dynamical solution (412) for the moving triad start at order

. One can check that precession effects in the above

dynamical solution (412) for the moving triad start at order  .

.

11.3 Spin-orbit effects in the gravitational wave flux and orbital phase

Like in Section 9 our main task is to control up to high post-Newtonian order the mass and current radiative

multipole moments  and

and  which parametrize the asymptotic waveform and gravitational fluxes far

away from the source, cf. Eqs. (66) – (68). The radiative multipole moments are in turn related to the source

multipole moments

which parametrize the asymptotic waveform and gravitational fluxes far

away from the source, cf. Eqs. (66) – (68). The radiative multipole moments are in turn related to the source

multipole moments  and

and  through complicated relationships involving tails and related effects; see e.g.,

Eqs. (76).86

through complicated relationships involving tails and related effects; see e.g.,

Eqs. (76).86

The source moments have been expressed in Eqs. (123) in terms of some source densities  ,

,  and

and

defined from the components of the post-Newtonian expansion of the pseudo-tensor,

denoted

defined from the components of the post-Newtonian expansion of the pseudo-tensor,

denoted  . To lowest order the (PN expansion of the) pseudo-tensor reduces to the matter

tensor

. To lowest order the (PN expansion of the) pseudo-tensor reduces to the matter

tensor  which has compact support, and the source densities

which has compact support, and the source densities  ,

,  ,

,  reduce to

the compact support quantities

reduce to

the compact support quantities  ,

,

given by Eqs. (145). Now, computing spin

effects, the matter tensor

given by Eqs. (145). Now, computing spin

effects, the matter tensor  has been found to be given by (378*) in the framework of the

pole-dipole approximation suitable for SO couplings (and sufficient also for SS interactions between

different spins). Here, to give a flavor of the computation, we present the lowest order spin

contributions (necessarily SO) to the general mass and current source multipole moments (

has been found to be given by (378*) in the framework of the

pole-dipole approximation suitable for SO couplings (and sufficient also for SS interactions between

different spins). Here, to give a flavor of the computation, we present the lowest order spin

contributions (necessarily SO) to the general mass and current source multipole moments ( ):

):

Paralleling the similar expressions (304) for the Newtonian approximation to the source moments in the

non-spin case, we posed  with

with  [see also Eqs. (305)]. In Eqs. (413)

we employ the notation (389) for the two spins and the ordinary cross product

[see also Eqs. (305)]. In Eqs. (413)

we employ the notation (389) for the two spins and the ordinary cross product  of Euclidean vectors.

Thus, the dominant level of spins is at the 1.5PN order in the mass-type moments

of Euclidean vectors.

Thus, the dominant level of spins is at the 1.5PN order in the mass-type moments  , but only at the

0.5PN order in the current-type moments

, but only at the

0.5PN order in the current-type moments  . It is then evident that the spin part of the current-type

moments will always dominate over that of the mass-type moments. We refer to [53*, 89*] for higher order

post-Newtonian expressions of the source moments. If we insert the expressions (413) into tail

integrals like (76), we find that some spin contributions originate from tails starting at the 3PN

order [54*].

. It is then evident that the spin part of the current-type

moments will always dominate over that of the mass-type moments. We refer to [53*, 89*] for higher order

post-Newtonian expressions of the source moments. If we insert the expressions (413) into tail

integrals like (76), we find that some spin contributions originate from tails starting at the 3PN

order [54*].

Finally, skipping details, we are left with the following highest-order known result for the SO contributions to the gravitational wave energy flux, which is currently 4PN order [53, 89*, 306]:87

We recall that  and

and  , with

, with  and

and  denoting the combinations (389), and

the individual spins are the specific conserved-norm spins that have been introduced in Section 11.1. The

result (414) superposes to the non-spin contributions given by Eq. (314). Satisfyingly it is in complete

agreement in the test-mass limit where

denoting the combinations (389), and

the individual spins are the specific conserved-norm spins that have been introduced in Section 11.1. The

result (414) superposes to the non-spin contributions given by Eq. (314). Satisfyingly it is in complete

agreement in the test-mass limit where  with the result of black-hole perturbation theory on a Kerr

background obtained in Ref. [396].

with the result of black-hole perturbation theory on a Kerr

background obtained in Ref. [396].

Finally we can compute the spin effects in the time evolution of the binary’s orbital frequency  . We

rely as in Section 9 on the equation (295*) balancing the total emitted energy flux

. We

rely as in Section 9 on the equation (295*) balancing the total emitted energy flux  with the variation of

the binary’s center-of-mass energy

with the variation of

the binary’s center-of-mass energy  . The non-spin contributions in

. The non-spin contributions in  have been provided for

quasi-circular binaries in Eq. (232); the SO contributions to next-to-next-to-leading order are given

by [307, 90]

have been provided for

quasi-circular binaries in Eq. (232); the SO contributions to next-to-next-to-leading order are given

by [307, 90]

Using  and

and  expressed as functions of the orbital frequency

expressed as functions of the orbital frequency  (through

(through  ) and of the spin

variables (through

) and of the spin

variables (through  and

and  ), we transform the balance equation into

), we transform the balance equation into

However, in writing the latter equation it is important to justify that the spin quantities  and

and  are secularly constant, i.e., do not evolve on a gravitational radiation reaction time scale so we can

neglect their variations when taking the time derivative of Eq. (415). Fortunately, this is the case

of the conserved-norm spin variables, as proved in Ref. [423] up to relative 1PN order, i.e.,

considering radiation reaction effects up to 3.5PN order. Furthermore this can also be shown

from the following structural general argument valid at linear order in spins [54, 89]. In the

center-of-mass frame, the only vectors at our disposal, except for the spins, are

are secularly constant, i.e., do not evolve on a gravitational radiation reaction time scale so we can

neglect their variations when taking the time derivative of Eq. (415). Fortunately, this is the case

of the conserved-norm spin variables, as proved in Ref. [423] up to relative 1PN order, i.e.,

considering radiation reaction effects up to 3.5PN order. Furthermore this can also be shown

from the following structural general argument valid at linear order in spins [54, 89]. In the

center-of-mass frame, the only vectors at our disposal, except for the spins, are  and

and  .

Recalling that the spin vectors are pseudovectors regarding parity transformation, we see that

the only way SO contributions can enter scalars such as the energy

.

Recalling that the spin vectors are pseudovectors regarding parity transformation, we see that

the only way SO contributions can enter scalars such as the energy  or the flux

or the flux  is

through the mixed products

is

through the mixed products  , i.e., through the components

, i.e., through the components  . Now, the same

reasoning applies to the precession vectors

. Now, the same

reasoning applies to the precession vectors  in Eqs. (388*): They must be pseudovectors,

and, at linear order in spin, they must only depend on

in Eqs. (388*): They must be pseudovectors,

and, at linear order in spin, they must only depend on  and

and  ; so that they must be

proportional to

; so that they must be

proportional to  , as can be explicitly seen for instance in Eq. (394). Now, the time derivative of

the components along

, as can be explicitly seen for instance in Eq. (394). Now, the time derivative of

the components along  of the spins are given by

of the spins are given by  . The

second term vanishes because

. The

second term vanishes because  , and since

, and since  , we obtain that

, we obtain that  is

constant at linear order in the spins. We have already met an instance of this important fact in

Eq. (409c). This argument is valid at any post-Newtonian order and for general orbits, but is

limited to spin-orbit terms; furthermore it does not specify any time scale for the variation, so it

applies to short time scales such as the orbital and precessional periods, as well as to the long

gravitational radiation reaction time scale (see also Ref. [218] and references therein for related

discussions).

is

constant at linear order in the spins. We have already met an instance of this important fact in

Eq. (409c). This argument is valid at any post-Newtonian order and for general orbits, but is

limited to spin-orbit terms; furthermore it does not specify any time scale for the variation, so it

applies to short time scales such as the orbital and precessional periods, as well as to the long

gravitational radiation reaction time scale (see also Ref. [218] and references therein for related

discussions).

[defined by

Eq. (319*)] for binaries detectable by ground-based detectors LIGO-VIRGO. The entry frequency

is

[defined by

Eq. (319*)] for binaries detectable by ground-based detectors LIGO-VIRGO. The entry frequency

is  and the terminal frequency is

and the terminal frequency is  . For each compact object

the magnitude

. For each compact object

the magnitude  and the orientation

and the orientation  of the spin are defined by

of the spin are defined by  and

and

; remind Eq. (366*). The spin-spin (SS) terms are neglected.

; remind Eq. (366*). The spin-spin (SS) terms are neglected.| PN order |  |

|

|

|

| 1.5PN | (leading SO) |  |

|

|

| 2.5PN | (1PN SO) |  |

|

|

| 3PN | (leading SO-tail) |  |

|

|

| 3.5PN | (2PN SO) |  |

|

|

| 4PN | (1PN SO-tail) |  |

|

|

We are then allowed to apply Eq. (416*) with conserved-norm spin variables at the SO level. We thus

obtain the secular evolution of  and from that we deduce by a further integration (following the Taylor

approximant T2) the secular evolution of the carrier phase

and from that we deduce by a further integration (following the Taylor

approximant T2) the secular evolution of the carrier phase  :

:

This expression, when added to the expression for the non-spin terms given by Eq. (318), and

considering also the SS terms, constitutes the main theoretical input needed for the construction of

templates for spinning compact binaries. However, recall that in the case of precessional binaries, for which

the spins are not aligned or anti-aligned with the orbital angular momentum, we must subtract to the

carrier phase  the precessional correction

the precessional correction  arising from the precession of the orbital plane. Indeed the

physical phase variable

arising from the precession of the orbital plane. Indeed the

physical phase variable  which is defined in Figure 4*, has been proved to be given by

which is defined in Figure 4*, has been proved to be given by  at

linear order in spins, cf. Eq. (405*). The precessional correction

at

linear order in spins, cf. Eq. (405*). The precessional correction  can be computed at linear order in

spins from the results of Section 11.2.

can be computed at linear order in

spins from the results of Section 11.2.

As we have done in Table 3 for the non-spin terms, we evaluate in Table 4 the SO contributions to the number of gravitational-wave cycles accumulated in the bandwidth of LIGO-VIRGO detectors, Eq. (319*). The results show that the SO terms up to 4PN order can be numerically important, for spins close to maximal and for suitable orientations. They can even be larger than the corresponding non-spin contributions at 3.5PN order and perhaps at 4PN order (but recall that the non-spin terms at 4PN order are not known); compare with Table 3. We thus conclude that the SO terms are relevant to be included in the gravitational wave templates for an accurate extraction of the binary parameters. Although numerically smaller, the SS terms are also relevant; for these we refer to the literature quoted at the beginning of Section 11.

![[ ] ∫ +∞ ( ) I yα,eA α = d τL u α,ωαβ,gαβ . (369 ) −∞](article2835x.gif)