3 Space-Based Missions to Detect Gravitational Waves

The experimental search for GWs began in the 1960s with Joseph Weber’s resonant bars (and resonant claims [124]); it has since grown into an extensive international endeavor that has produced a network of km-scale GW interferometers (LIGO [288], EGO/VIRGO [167], GEO600 [203], and Tama/KAGRA [254]), the proposals for space-based observatories such as LISA, and the effort to detect GWs by using an array of pulsars as reference clocks [232]. In this section we briefly describe the architecture of LISA-like space-based GW observatories, beginning

with the “classic” LISA design, and then discussing the variations studied in the 2011 – 2012 ESA and

NASA studies [20, 215 ]. We also discuss proposals for detectors that would operate in a higher frequency

band (between 0.1 and 10 Hz) that would bridge the gap in sensitivity between LISA-like and ground-based

observatories.

]. We also discuss proposals for detectors that would operate in a higher frequency

band (between 0.1 and 10 Hz) that would bridge the gap in sensitivity between LISA-like and ground-based

observatories.

3.1 The classic LISA architecture

The most cited LISA reference is perhaps the 1998 pre-phase A mission study [64]; a more up-to-date

review of the LISA technical architecture is given by Jennrich [252 ], while the LISA science-case

document [370] describes the state of LISA science at the end of the 2000s. Here we give only a

quick review of the elements of the mission, referring the reader to those references for in-depth

discussions.

], while the LISA science-case

document [370] describes the state of LISA science at the end of the 2000s. Here we give only a

quick review of the elements of the mission, referring the reader to those references for in-depth

discussions.

LISA principles.

LISA consists of three identical cylindrical spacecraft, approximately 3 m wide and 1 m high, that are launched together and, after a 14-month cruise, settle into an Earth-like heliocentric orbit, 20° behind the Earth. The orbit of each spacecraft is tuned slightly differently, resulting in an equilateral-triangle configuration with arms (commensurate with the

frequencies of the LISA sensitivity band), inclined by 60° with respect to the ecliptic. This

configuration is maintained to 1% by orbital dynamics alone for the lifetime of the mission, nominally

5 years, with a goal of 10. In the course of a year, the center of the LISA triangle completes a full

revolution on the ecliptic, while the triangle itself, as well as its normal vector, rotate through

360°.

LISA detects GWs by monitoring the fluctuations in the distances between freely-falling reference bodies

– in LISA, platinum-gold test masses housed and protected by the spacecraft. LISA uses three pairs of laser

interferometric links to measure inter-spacecraft distances with errors near

arms (commensurate with the

frequencies of the LISA sensitivity band), inclined by 60° with respect to the ecliptic. This

configuration is maintained to 1% by orbital dynamics alone for the lifetime of the mission, nominally

5 years, with a goal of 10. In the course of a year, the center of the LISA triangle completes a full

revolution on the ecliptic, while the triangle itself, as well as its normal vector, rotate through

360°.

LISA detects GWs by monitoring the fluctuations in the distances between freely-falling reference bodies

– in LISA, platinum-gold test masses housed and protected by the spacecraft. LISA uses three pairs of laser

interferometric links to measure inter-spacecraft distances with errors near  . The phase shifts

accumulated along different interferometer paths are proportional to an integral of GW strain along those

trajectories. The test masses suffer from residual acceleration noise at a level of

. The phase shifts

accumulated along different interferometer paths are proportional to an integral of GW strain along those

trajectories. The test masses suffer from residual acceleration noise at a level of  , which is

dominant below 3 mHz. Together, the position and acceleration noises (divided by a multiple of the

armlength) determine the LISA sensitivity to GW strain, which reaches

, which is

dominant below 3 mHz. Together, the position and acceleration noises (divided by a multiple of the

armlength) determine the LISA sensitivity to GW strain, which reaches  at frequencies of a

few mHz.

at frequencies of a

few mHz.

Alternatively (but equivalently), we may describe LISA as measuring the GW-induced relative Doppler shifts between the local lasers on each spacecraft and the remote lasers. These Doppler shifts are directly proportional to a difference of instantaneous GW strains (as experienced by the local spacecraft at the time of measurement, and by the distant spacecraft at a time retarded by the LISA armlength divided by the speed of light). In either description, the 1% “breathing” of the LISA constellation occurs at frequencies that are safely below the LISA measurement band.

LISA technology.

The distance measurement between the test masses along each arm is in fact split in three: an inter-spacecraft measurement between the two optical benches, and two local measurements between each test mass and its optical bench. To achieve the inter-spacecraft measurement, 2 W of 1064-nm light are sent and received through 40-cm telescopes. The diffracted beams deliver only 100 pW of light to the distant spacecrafts, so they cannot be reflected directly; instead, the laser phase is measured and transponded back by modulating the frequency of the local lasers. Each of the two optical assemblies on each spacecraft include the telescope and a Zerodur optical bench with bonded fused-silica optical components, which implements the inter-spacecraft and local interferometers, as well as a few auxiliary interferometric measurements, which are needed to monitor the stability of the telescope structure, to control point-ahead corrections, and to compare the two lasers on each spacecraft. The LISA phasemeters digitize the signals from the optical-bench photodetectors at 50 MHz, and multiply them with the output of local oscillators, computing phase differences and driving the oscillators to track the frequency of the measured signal. This heterodyne scheme is needed to handle Doppler shifts (as well as laser frequency offsets) as large as 15 MHz. Because intrinsic fluctuations in the laser frequencies are indistinguishable from GWs in the LISA output, laser frequency noise needs to be suppressed by several orders of magnitude, using a hierarchy of techniques [252]: the lasers are prestabilized to local frequency references; arm locking may be used to further stabilize the lasers using the LISA arms (or their differences) as stable references; finally, Time-Delay Interferometry [149] is applied in post processing to remove residual laser frequency noise by algebraically combining appropriately-delayed single-link measurements, in such a way that all laser-frequency–noise terms appear as canceling pairs in the combination. With this final step, the LISA measurements combine into synthesized-interferometer observables [447] analogous to the readings of ground-based interferometers such as LIGO. The LISA disturbance reduction system (DRS) minimizes the deviations of the test masses from free-fall

trajectories, by shielding them from solar radiation pressure and interplanetary magnetic fields. On each

spacecraft, the DRS includes two gravitational reference sensors (GRSs): a GRS consists of a 2-kg test

mass, enclosed in an electrode housing with capacitive reading and control of test-mass position

and orientation, and accompanied by additional components to cage and reposition the test

mass, to maintain vacuum, and to control the accumulation of charge. The other crucial part of

the DRS are the micro-Newton thrusters (on each spacecraft, three clusters of four colloid or

field-emission–electric propulsion systems), which are controlled in response to the GRS readings to

maintain the nominal position of the test mass with respect to the spacecraft. This is known as

drag-free control. The thrusters need to provide up to  force with

force with  noise. In

addition to this active correction, test-mass acceleration noise is minimized by the accurate

knowledge and correction of spacecraft self-gravity, by enforcing magnetic cleanliness, and by

controlling thermal fluctuations. A version of the LISA DRS with slightly lower performance will

be flown and tested in LISA Pathfinder [305, 25], a single-spacecraft technology precursor

mission.

noise. In

addition to this active correction, test-mass acceleration noise is minimized by the accurate

knowledge and correction of spacecraft self-gravity, by enforcing magnetic cleanliness, and by

controlling thermal fluctuations. A version of the LISA DRS with slightly lower performance will

be flown and tested in LISA Pathfinder [305, 25], a single-spacecraft technology precursor

mission.

The LISA response to GWs.

Compared to ground-based interferometers, the LISA response to GWs is both richer and more complex [166, 462, 448, 133]. First, the revolution and rotation of the LISA constellation imprint a sky-position–dependent signature on long-lasting GW signals (which for LISA include all binary signals): the revolution causes a time-dependent Doppler shift with a period of a year, and a fractional amplitude of ; the rotation introduces a 1-year periodicity in the LISA equivalent of the

ground-based–interferometer antenna patterns [299], endowing an incoming monochromatic GW

signal with eight sidebands, separated by

; the rotation introduces a 1-year periodicity in the LISA equivalent of the

ground-based–interferometer antenna patterns [299], endowing an incoming monochromatic GW

signal with eight sidebands, separated by  . These effects are sometimes

referred to as the LISA AM and FM modulations. Thus, GW signals as measured by LISA carry

information regarding the position of the source; on the other hand, data analysis must account for

these effects, possibly including sky position among the parameters of matched-filtering search

templates.

Second, the long-wavelength approximation, whereby the entire “interferometer” shrinks and expands as

one, cannot be used throughout the LISA band; indeed, the wavelength of GWs reaches the LISA

armlength at a frequency of 60 mHz. As a consequence, the LISA response to a few-second

impulsive GW is not a single pulse, but a collection of pulses with amplitudes and separations

dependent on the sky position and polarization of the source; the effect on high-frequency chirping

signals is more subtle, but still present. This further complicates data analysis, and introduces an

independent mechanism (a triangulation of sorts) to localize GW sources of short duration and high

frequency.

. These effects are sometimes

referred to as the LISA AM and FM modulations. Thus, GW signals as measured by LISA carry

information regarding the position of the source; on the other hand, data analysis must account for

these effects, possibly including sky position among the parameters of matched-filtering search

templates.

Second, the long-wavelength approximation, whereby the entire “interferometer” shrinks and expands as

one, cannot be used throughout the LISA band; indeed, the wavelength of GWs reaches the LISA

armlength at a frequency of 60 mHz. As a consequence, the LISA response to a few-second

impulsive GW is not a single pulse, but a collection of pulses with amplitudes and separations

dependent on the sky position and polarization of the source; the effect on high-frequency chirping

signals is more subtle, but still present. This further complicates data analysis, and introduces an

independent mechanism (a triangulation of sorts) to localize GW sources of short duration and high

frequency.

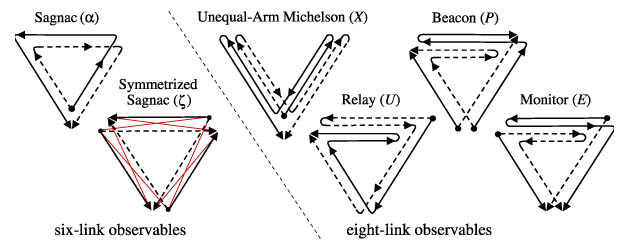

Third, LISA is in effect three detectors in one: this can be understood most easily by considering that

subsets of the three LISA arms form three separate Michelson-like interferometers (known in LISA lingo as

,

,  , and

, and  ) at 120° angles. More formally, the LISA interferometric measurements can be

combined into many different TDI observables (see Figure 1

) at 120° angles. More formally, the LISA interferometric measurements can be

combined into many different TDI observables (see Figure 1 ), some resembling actual optical setups, others

quite exotic [447], although at most three observables are independent in the sense that any

other observable can be reconstructed by time-delaying and summing a generic basis of three

observables [452]. Furthermore, such a basis can be chosen so that its components have uncorrelated

noises, much like widely separated ground-based detectors [369]. One of these must correspond,

in effect, to

), some resembling actual optical setups, others

quite exotic [447], although at most three observables are independent in the sense that any

other observable can be reconstructed by time-delaying and summing a generic basis of three

observables [452]. Furthermore, such a basis can be chosen so that its components have uncorrelated

noises, much like widely separated ground-based detectors [369]. One of these must correspond,

in effect, to  , and by symmetry it must be relatively insensitive to GWs in the

long-wavelength limit, providing for an independent measurement of a combination of instrument

noises.

, and by symmetry it must be relatively insensitive to GWs in the

long-wavelength limit, providing for an independent measurement of a combination of instrument

noises.

3.2 LISA-like observatories

The mission-concept studies ran in 2011 – 2012 by ESA [20] and NASA [215 ] embrace several approaches to

limiting cost.

] embrace several approaches to

limiting cost.

Reducing mass is a broadly useful strategy, because it allows for launch on smaller, cheaper rockets, and because mass has been shown to be a good proxy for mission complexity, and therefore implementation cost. ESA’s NGO design envisages interferometric links along two arms rather than LISA’s three, resulting in an asymmetric configuration with one full and two “half” spacecraft. As a consequence, only one TDI observable can be formed, eliminating the capability of measuring two combinations of GW polarizations simultaneously.

Propellant may be saved by placing the spacecraft closer together (with arms  1 – 3 Mkm rather

than 5 Mkm) and closer to Earth. At low frequencies, the effect of shorter armlengths is to reduce

the response to GWs proportionally; for the same test-mass noise, sensitivity then decreases

by the same ratio. At high frequencies, the laser power available for position measurement

increases as

1 – 3 Mkm rather

than 5 Mkm) and closer to Earth. At low frequencies, the effect of shorter armlengths is to reduce

the response to GWs proportionally; for the same test-mass noise, sensitivity then decreases

by the same ratio. At high frequencies, the laser power available for position measurement

increases as  , since beams are broadly defocused at millions of kms, improving shot noise,

but not other optical noises, by a factor

, since beams are broadly defocused at millions of kms, improving shot noise,

but not other optical noises, by a factor  (in rms). As a consequence, the sweet spot

of the LISA sensitivity shifts to higher frequencies, although one may instead plan for a less

powerful laser, for further cost savings. Spacecraft orbits that are different than LISA’s, such as

geocentric options, or flat configurations that lie in the ecliptic plane would also alter GW-signal

modulations, and therefore parameter-estimation performance. The NASA report examines such effects

briefly [215

(in rms). As a consequence, the sweet spot

of the LISA sensitivity shifts to higher frequencies, although one may instead plan for a less

powerful laser, for further cost savings. Spacecraft orbits that are different than LISA’s, such as

geocentric options, or flat configurations that lie in the ecliptic plane would also alter GW-signal

modulations, and therefore parameter-estimation performance. The NASA report examines such effects

briefly [215 ].

].

Reducing mission duration also saves money, because it reduces the cost of supporting the mission from the ground, and it allows for shorter “warranties” on the various subsystems. Conversely, missions are made cheaper by accepting more risk of failure or underperformance, since risk is “retired” by extensive testing and by introducing component redundancy, both of which are expensive. The NASA study also explored replacing LISA’s custom subsystems with variants already flown on other missions (as in OMEGA [229]), or eliminating some of them altogether (as in LAGRANGE [304]). However, the significant performance hit and additional risk incurred by such steps is not matched by correspondingly major savings, because the main cost driver for LISA-like missions is the necessity of launching and flying three (or more) independent spacecraft. Switching to atom interferometry would make for very different mission architectures, but the NASA study finds that an atom-interferometer mission would face many of the same cost-driving constraints as a laser-interferometer mission [215, 43].

Indeed, the overarching conclusion of the NASA study is that no technology can provide dramatic cost reductions, and that scientific performance decreases far more rapidly than cost. Thus, “staying the course” and pursuing a modestly descoped LISA-like design, whenever programs and budgets will allow it, may yet be the most promising strategy for GW detection in space.

3.3 Mid-frequency space-based observatories

The DECi-hertz Interferometer Gravitational wave Observatory (DECIGO [408, 256, 257]) is a proposed

Japanese mission that would observe GWs at frequencies between 1 mHz and 100 Hz, reaching its best

( ) sensitivity between 0.1 and 10 Hz, and thus bridging the gap between LISA-like and

ground-based detectors. Prior to DECIGO, the possibility of observing GWs in the decihertz

band had been studied in the context of a possible follow-up to LISA, the Big Bang Observer

(BBO [357, 135, 138]).

) sensitivity between 0.1 and 10 Hz, and thus bridging the gap between LISA-like and

ground-based detectors. Prior to DECIGO, the possibility of observing GWs in the decihertz

band had been studied in the context of a possible follow-up to LISA, the Big Bang Observer

(BBO [357, 135, 138]).

The final DECIGO configuration (2024+) envisages four clusters in an Earth-like solar orbit, each

cluster consisting of three drag-free spacecraft in a triangle with 1000-km arms. GWs are measured by

operating the arms as a Fabry–Pérot interferometer, which requires keeping the armlengths constant, in

analogy to ground-based interferometers and in contrast to LISA’s transponding scheme. DECIGO’s test

masses are 100 kg mirrors, and its lasers have 10 W power. The roadmap toward DECIGO includes two

pathfinders: the single-spacecraft DECIGO Pathfinder [23] consists of a 30 cm Fabry–Pérot cavity, and it

could detect binaries of  black holes if they exist near the galaxy [480]; next,

pre-DECIGO [257] would demonstrate the DECIGO measurement with three spacecraft and modest

optical parameters, resulting in a sensitivity 10 – 100 times worse than one of the final DECIGO

clusters.

black holes if they exist near the galaxy [480]; next,

pre-DECIGO [257] would demonstrate the DECIGO measurement with three spacecraft and modest

optical parameters, resulting in a sensitivity 10 – 100 times worse than one of the final DECIGO

clusters.

The DECIGO science objectives [257] include measuring the GW stochastic background from

“standard” inflation (with sensitivity down to  ), and determining the thermal history of

the universe between the end of inflation and nucleosynthesis [325, 274]; searching for hypothesized

primordial black holes [390]; characterizing dark energy by using neutron-star binaries as standard candles

(either with host redshifts [333], or by the effect of cosmic expansion on the inspiral phasing [408, 334]);

illuminating the formation of massive galactic black holes by observing the coalescences of

intermediate-mass (

), and determining the thermal history of

the universe between the end of inflation and nucleosynthesis [325, 274]; searching for hypothesized

primordial black holes [390]; characterizing dark energy by using neutron-star binaries as standard candles

(either with host redshifts [333], or by the effect of cosmic expansion on the inspiral phasing [408, 334]);

illuminating the formation of massive galactic black holes by observing the coalescences of

intermediate-mass ( ) systems; constraining the structure of neutron stars by measuring their

masses (in upwards of 100 000 detections per year); and even searching for planets orbiting neutron-star

binaries.

) systems; constraining the structure of neutron stars by measuring their

masses (in upwards of 100 000 detections per year); and even searching for planets orbiting neutron-star

binaries.

DECIGO can also test alternative theories of gravity, as reviewed in [482]: by observing neutron-star–intermediate-mass-black-hole systems, it can constrain the dipolar radiation predicted in Brans–Dicke scalar-tensor theory (see Section 5.1.3 in this review) better than LISA, and four orders of magnitude better than solar-system experiments [486]; it can constrain the speed of GWs, parametrized as the mass of the graviton (Section 5.1.2) three orders of magnitude better than solar-system experiments, although not as well as LISA [486]; by observing binaries of neutron stars and stellar-mass black holes, it can constrain the Einstein-Dilaton-Gauss–Bonnet [481] and dynamical Chern–Simons [487] theories; it can measure the bulk AdS curvature scale that modifies the evolution of black-hole binaries in the Randall–Sundrum II braneworld model [484]; and it can even look for extra polarization modes (Section 5.1.1) in the stochastic GW background [332].

In the rest of this review we concentrate on the tests of GR that will be possible with low-, rather than mid-frequency GW observatories. Nevertheless, many of the studies performed for LISA-like detectors are easily extended to the ambitious DECIGO program, which would probe GW sources of similar nature, but of different masses or in different phases of their evolution.