4 Testing Techniques

4.1 Coalescence analysis

Gravitational waves emitted during the inspiral, merger and ringdown of compact binaries are the most studied in the context of data analysis and parameter estimation. In this section, we will review some of the main data analysis techniques employed in the context of parameter estimation and tests of GR. We begin with a discussion of matched filtering and Fisher theory (for a detailed review, see [173, 103, 125*, 174*, 248]). We then continue with a discussion of Bayesian parameter estimation and hypothesis testing (for a detailed review, see [387, 205, 123, 294*]).

4.1.1 Matched filtering and Fisher’s analysis

When the detector noise  is Gaussian and stationary, and when the signal

is Gaussian and stationary, and when the signal  is known very well,

the optimal detection strategy is matched filtering. For any given realization, such noise can be

characterized by its power spectral density

is known very well,

the optimal detection strategy is matched filtering. For any given realization, such noise can be

characterized by its power spectral density  , defined via

, defined via

The detectability of a signal is determined by its signal-to-noise ratio or SNR, which is defined via

where is a template with parameters

is a template with parameters  and we have defined the inner product

If the templates do not exactly match the signal, then the SNR is reduced by a factor of

and we have defined the inner product

If the templates do not exactly match the signal, then the SNR is reduced by a factor of  , called the

match:

where

, called the

match:

where  is the mismatch.

is the mismatch.

For the noise assumptions made here, the probability of measuring  in the detector output, given a

template

in the detector output, given a

template  , is given by

, is given by

that best fits the signal is that with best-fit parameters such that the argument

of the exponential is minimized. For large SNR, the best-fit parameters will have a multivariate Gaussian

distribution centered on the true values of the signal

that best fits the signal is that with best-fit parameters such that the argument

of the exponential is minimized. For large SNR, the best-fit parameters will have a multivariate Gaussian

distribution centered on the true values of the signal  , and thus, the waveform parameters that best fit

the signal minimize the argument of the exponential. The parameter errors

, and thus, the waveform parameters that best fit

the signal minimize the argument of the exponential. The parameter errors  will be distributed

according to

where

will be distributed

according to

where  is the Fisher matrix

The root-mean-squared (

is the Fisher matrix

The root-mean-squared ( ) error on a given parameter

) error on a given parameter  is then

where

is then

where  is the variance-covariance matrix and summation is not implied in Eq. (83*) (

is the variance-covariance matrix and summation is not implied in Eq. (83*) ( denotes a particular element of the vector

denotes a particular element of the vector  ). This root-mean-squared error is sometimes referred to as

the statistical error in the measurement of

). This root-mean-squared error is sometimes referred to as

the statistical error in the measurement of  . One can use Eq. (83*) to estimate how well modified gravity

parameters can be measured. Put another way, if a gravitational wave were detected and found consistent

with GR, Eq. (83*) would provide an estimate of how close to zero these modified gravity parameters would

have to be.

. One can use Eq. (83*) to estimate how well modified gravity

parameters can be measured. Put another way, if a gravitational wave were detected and found consistent

with GR, Eq. (83*) would provide an estimate of how close to zero these modified gravity parameters would

have to be.

The Fisher method to estimate projected constraints on modified gravity theory parameters is as

follows. First, one constructs a waveform model in the particular modified gravity theory one wishes to

constrain. Usually, this waveform will be similar to the GR one, but it will contain an additional parameter,

, such that the template parameters are now

, such that the template parameters are now  plus

plus  . Let us assume that as

. Let us assume that as  , the modified

gravity waveform reduces to the GR expectation. Then, the accuracy to which

, the modified

gravity waveform reduces to the GR expectation. Then, the accuracy to which  can be measured, or

the accuracy to which we can say

can be measured, or

the accuracy to which we can say  is zero, is approximately

is zero, is approximately  , where the Fisher

matrix associated with this variance-covariance matrix must be computed with the non-GR

model evaluated at the GR limit (

, where the Fisher

matrix associated with this variance-covariance matrix must be computed with the non-GR

model evaluated at the GR limit ( ). Such a method for estimating how well modified

gravity theories can be constrained was pioneered by Will in [436*, 353], and since then, it has

been widely employed as a first-cut estimate of the accuracy to which different theories can be

constrained.

). Such a method for estimating how well modified

gravity theories can be constrained was pioneered by Will in [436*, 353], and since then, it has

been widely employed as a first-cut estimate of the accuracy to which different theories can be

constrained.

The Fisher method described above can dangerously lead to incorrect results if abused [414, 415]. One

must understand that this method is suitable only if the noise is stationary and Gaussian and if the SNR is

sufficiently large. How large an SNR is required for Fisher methods to work depends somewhat on the

signals considered, but usually for applications concerning tests of GR, one would be safe with  or

so. In real data analysis, the first two conditions are almost never satisfied. Moreover, the first

detections that will be made will probably be of low SNR, i.e.,

or

so. In real data analysis, the first two conditions are almost never satisfied. Moreover, the first

detections that will be made will probably be of low SNR, i.e.,  , for which again the

Fisher method fails. In such cases, more sophisticated parameter estimation methods need to be

employed.

, for which again the

Fisher method fails. In such cases, more sophisticated parameter estimation methods need to be

employed.

4.1.2 Bayesian theory and model testing

Bayesian theory is ideal for parameter estimation and model selection. Let us then assume that a detection

has been made and that the gravitational wave signal in the data can be described by some model  ,

parameterized by the vector

,

parameterized by the vector  . Using Bayes’ theorem, the posterior distribution function (PDF) or

the probability density function for the model parameters, given data

. Using Bayes’ theorem, the posterior distribution function (PDF) or

the probability density function for the model parameters, given data  and model

and model  , is

, is

represents our prior beliefs of the parameter

range in model

represents our prior beliefs of the parameter

range in model  . The marginalized likelihood or evidence, is the normalization constant

which clearly guarantees that the integral of Eq. (84*) integrates to unity. The quantity

. The marginalized likelihood or evidence, is the normalization constant

which clearly guarantees that the integral of Eq. (84*) integrates to unity. The quantity  is the

likelihood function, which is simply given by Eq. (80*), with a given normalization. In that equation we used

slightly different notation, with

is the

likelihood function, which is simply given by Eq. (80*), with a given normalization. In that equation we used

slightly different notation, with  being the data

being the data  and

and  the template associated with model

the template associated with model  and parameterized by

and parameterized by  . The marginalized PDF, which represents the probability density function for a

given parameter

. The marginalized PDF, which represents the probability density function for a

given parameter  (recall that

(recall that  is a particular element of

is a particular element of  ), after marginalizing over all other

parameters, is given by

where the integration is not to be carried out over

), after marginalizing over all other

parameters, is given by

where the integration is not to be carried out over  .

.

Let us now switch gears to model selection. In hypothesis testing, one wishes to determine whether the

data is more consistent with hypothesis A (e.g., that a GR waveform correctly models the signal) or with

hypothesis B (e.g., that a non-GR waveform correctly models the signal). Using Bayes’ theorem, the PDF

for model  given the data is

given the data is

is the prior probability of hypothesis

is the prior probability of hypothesis  , namely the strength of our prior belief that

hypothesis

, namely the strength of our prior belief that

hypothesis  is correct. The normalization constant

is correct. The normalization constant  is given by

where the integral is to be taken over all models. Thus, it is clear that this normalization constant does

not depend on the model. Similar relations hold for hypothesis

is given by

where the integral is to be taken over all models. Thus, it is clear that this normalization constant does

not depend on the model. Similar relations hold for hypothesis  by replacing

by replacing  in

Eq. (87*).

in

Eq. (87*).

When hypothesis A and B refer to fundamental theories of nature we can take different viewpoints

regarding the priors. If we argue that we know nothing about whether hypothesis A or B better describes

nature, then we would assign equal priors to both hypotheses. If, on the other hand, we believe GR is the

correct theory of nature, based on all previous experiments performed in the solar system and with binary

pulsars, then we would assign  . This assigning of priors necessarily biases the inferences

derived from the calculated posteriors, which is sometimes heavily debated when comparing Bayesian theory

to a frequentist approach. However, this “biasing” is really unavoidable and merely a reflection of

our state of knowledge of nature (for a more detailed discussion on such issues, please refer

to [294]).

. This assigning of priors necessarily biases the inferences

derived from the calculated posteriors, which is sometimes heavily debated when comparing Bayesian theory

to a frequentist approach. However, this “biasing” is really unavoidable and merely a reflection of

our state of knowledge of nature (for a more detailed discussion on such issues, please refer

to [294]).

The integral over all models in Eq. (88*) can never be calculated in practice, simply because

we do not know all models. Thus, one is forced to investigate relative probabilities between

models, such that the normalization constant  cancels out. The odds ratio is defined by

cancels out. The odds ratio is defined by

is the Bayes factor and the prefactor

is the Bayes factor and the prefactor  is the prior odds. The

odds-ratio is a convenient quantity to calculate because the evidence

is the prior odds. The

odds-ratio is a convenient quantity to calculate because the evidence  , which is difficult to compute,

actually cancels out. Recently, Vallisneri [416] has investigated the possibility of calculating the odds-ratio

using only frequentist tools and without having to compute full evidences. The odds-ratio should

be interpreted as the betting-odds of model

, which is difficult to compute,

actually cancels out. Recently, Vallisneri [416] has investigated the possibility of calculating the odds-ratio

using only frequentist tools and without having to compute full evidences. The odds-ratio should

be interpreted as the betting-odds of model  over model

over model  . For example, an odds-ratio

of unity means that both models are equally supported by the data, while an odds-ratio of

. For example, an odds-ratio

of unity means that both models are equally supported by the data, while an odds-ratio of

means that there is a 100 to 1 odds that model

means that there is a 100 to 1 odds that model  better describes the data than model

better describes the data than model

.

.

The main difficulty in Bayesian inference (both in parameter estimation and model selection) is sampling the PDF sufficiently accurately. Several methods have been developed for this purpose, but currently the two main workhorses in gravitational-wave data analysis are Markov Chain Monte Carlo and Nested Sampling. In the former, one samples the likelihood through the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm [314, 221, 122, 367]. This is computationally expensive in high-dimensional cases, and thus, there are several techniques to improve the efficiency of the method, e.g., parallel tempering [402]. Once the PDF has been sampled, one can then calculate the evidence integral, for example via thermodynamic integration [420, 167, 419]. In Nested Sampling, the evidence is calculated directly by laying out a fixed number of points in the prior volume, which are then allowed to move and coalesce toward regions of high posterior probability. With the evidence in hand, one can then infer the PDF. As in the previous case, Nested Sampling can be computationally expensive in high-dimensional cases.

Del Pozzo et al. [142*] were the first to carry out a Bayesian implementation of model selection in the context of tests of GR. Their analysis focused on tests of a particular massive graviton theory, using the gravitational wave signal from quasi-circular inspiral of non-spinning black holes. Cornish et al. [124*, 376*] extended this analysis by considering model-independent deviations from GR, using the parameterized post-Einsteinian (ppE) approach (Section 5.3.4) [467*]. Recently, this was continued by Li et al. [290*, 291], who carried out a similar analysis on a large statistical sample of Advanced LIGO (aLIGO) detections using simulated data and a restricted ppE model. All of these studies suggest that Bayesian tests of GR are possible, given sufficiently-high SNR events. Of course, whether deviations from GR are observable will depend on the strong-field character and strength of the deviation, as well as the availability of sufficiently-accurate GR waveforms.

4.1.3 Systematics in model selection

The model selection techniques described above are affected by other systematics present in data analysis. In general, we can classify these into the following [417*]:

- Mismodeling Systematic, caused by inaccurate models of the gravitational-wave template.

- Instrumental Systematic, caused by inaccurate models of the gravitational-wave response.

- Astrophysical Systematic, caused by inaccurate models of the astrophysical environment.

Mismodeling systematics are introduced due to the lack of an exact solution to the Einstein equations from which to extract an exact template, given a particular astrophysical scenario. Inspiral templates, for example, are approximated through post-Newtonian theory and become increasingly less accurate as the binary components approach each other. Cutler and Vallisneri [127] were the first to carry out a formal and practical investigation of such a systematic in the context of parameter estimation from a frequentist approach.

Mismodeling systematics will prevent us from testing GR effectively with signals that we do not understand sufficiently well. For example, when considering signals from black hole coalescences, if the the total mass of the binary is sufficiently high, the binary will merge in band. The higher the total mass, the fewer the inspiral cycles that will be in band, until eventually only the merger is in band. Since the merger phase is the least understood phase, it stands to reason that our ability to test GR will deteriorate as the total mass increases. Of course, we do understand the ringdown phase very well, and tests of the no-hair theorem would be allowed during this phase, provided a sufficiently-high SNR [65*]. On the other hand, for neutron star binaries or very–low-mass black-hole binaries, the merger phase is expected to be essentially out of band for aLIGO (above 1 kHz), and thus, the noise spectrum itself may shield us from our ignorance.

Instrumental systematics are introduced by our ignorance of the transfer function, which connects the detector output to the incoming gravitational waves. Through sophisticated calibration studies with real data, one can approximate the transfer function very well [4*, 1]. However, this function is not time-independent, because the noise in the instrument is not stationary or Gaussian. Thus, un-modeled drifts in the transfer function can introduce systematics in parameter estimation that are as large as 10% in the amplitude and the phase [4].

Instrumental systematics can affect tests of GR, if these are performed with a single instrument. However, one expects multiple detectors to be online in the future and for gravitational-wave detections to be made in several of them simultaneously. Instrumental systematics should be present in all such detections, but since the noise will be mostly uncorrelated between different instruments, one should be able to ameliorate its effects through cross-correlating outputs from several instruments.

Astrophysical systematics are induced by our lack of a priori knowledge of the gravitational wave source. As explained above, matched filtering requires knowledge of a waveform template with which to filter the data. Usually, we assume the sources are in a perfect vacuum and isolated. For example, when considering inspiral signals, we ignore any third bodies, electric or magnetic fields, neutron star hydrodynamics, the expansion of the universe, etc. Fortunately, however, most of these effects are expected to be small: the probability of finding third bodies sufficiently close to a binary system is very small [463*]; for low redshift events, the expansion of the universe induces an acceleration of the center of mass, which is also very small [468*]; electromagnetic fields and neutron-star hydrodynamic effects may affect the inspiral of black holes and neutron stars, but not until the very last stages, when most signals will be out of band anyways. For example, tidal deformation effects enter a neutron-star–binary inspiral waveform at 5 post-Newtonian order, which therefore affects the signal outside of the most sensitive part of the aLIGO sensitivity bucket.

Perhaps the most dangerous source of astrophysical systematics is due to the assumptions made about the astrophysical systems we expect to observe. For example, when considering neutron-star–binary inspirals, one usually assumes the orbit will have circularized by the time it enters the sensitivity band. Moreover, one assumes that any residual spin angular momentum that the neutron stars may possess is very small and aligned or counter-aligned with the orbital angular momentum. These assumptions certainly simplify the construction of waveform templates, but if they happen to be wrong, they would introduce mismodeling systematics that could also affect parameter estimation and tests of GR.

4.2 Burst analyses

In alternative theories of gravity, gravitational-wave sources such as core collapse supernovae may result in the production of gravitational waves in more than just the plus and cross-polarizations [384, 380, 216, 334, 333, 369]. Indeed, the near-spherical geometry of the collapse can be a source of scalar breathing-mode gravitational waves. However, the precise form of the waveform is unknown because it is sensitive to the initial conditions.

When searching for un-modeled bursts in alternative theories of gravity, a general approach involves

optimized linear combinations of data streams from all available detectors to form maximum likelihood

estimates of the waveforms in the various polarizations, and the use of null streams. In the context of

ground-based detectors and GR, these ideas were first explored by Gürsel and Tinto [212*] and later by

Chatterji et al. [101*] with the aim of separating false-alarm events from real detections. The main idea was

to construct a linear combination of data streams received by a network of detectors, so that the

combination contained only noise. Of course, in GR one need only include  and

and  polarizations, and

thus a network of three detectors suffices. This concept can be extended to develop null tests of GR, as

originally proposed by Chatziioannou et al. [102*] and recently implemented by Hayama et

al. [228*].

polarizations, and

thus a network of three detectors suffices. This concept can be extended to develop null tests of GR, as

originally proposed by Chatziioannou et al. [102*] and recently implemented by Hayama et

al. [228*].

Let us consider a network of  detectors with uncorrelated noise and a detection by all

detectors with uncorrelated noise and a detection by all  detectors. For a source that emits gravitational waves in the direction

detectors. For a source that emits gravitational waves in the direction  , a single data point (either in the

time-domain, or a time-frequency pixel) from an array of

, a single data point (either in the

time-domain, or a time-frequency pixel) from an array of  detectors (either pulsars or interferometers)

can be written as

detectors (either pulsars or interferometers)

can be written as

is a vector with the noise. The antenna pattern functions are given by the matrix,

For simplicity we have suppressed the sky-location dependence of the antenna pattern functions. These can

either be the interferometric antenna pattern functions in Eqs. (58*), or the pulsar response functions in

Eqs. (69*). For interferometers, since the breathing and longitudinal antenna pattern response functions are

degenerate, and even though

is a vector with the noise. The antenna pattern functions are given by the matrix,

For simplicity we have suppressed the sky-location dependence of the antenna pattern functions. These can

either be the interferometric antenna pattern functions in Eqs. (58*), or the pulsar response functions in

Eqs. (69*). For interferometers, since the breathing and longitudinal antenna pattern response functions are

degenerate, and even though  is a

is a  matrix, there are only five linearly-independent

vectors [81, 80, 102*, 228*].

matrix, there are only five linearly-independent

vectors [81, 80, 102*, 228*].

If we do not know the form of the signal present in our data, we can obtain maximum likelihood

estimators for it. For simplicity, let us assume the data are Gaussian and of unit variance (the latter can be

achieved by whitening the data). Just as we did in Eq. (80*), we can write the probability of obtaining

datum  , in the presence of a gravitational wave

, in the presence of a gravitational wave  as

as

is a projection operator that projects the data into the subspace spanned by

is a projection operator that projects the data into the subspace spanned by  . An

orthogonal projector can also be constructed,

which projects the data onto a sub-space orthogonal to

. An

orthogonal projector can also be constructed,

which projects the data onto a sub-space orthogonal to  . Thus one can construct a certain linear

combination of data streams that has no component of a certain polarization by projecting them to a

direction orthogonal to the direction defined by the beam pattern functions of this polarization mode

This is called a null stream and, in the context of GR, it was introduced as a means of separating

false-alarm events due, say, to instrumental glitches from real detections [212*, 101*].

. Thus one can construct a certain linear

combination of data streams that has no component of a certain polarization by projecting them to a

direction orthogonal to the direction defined by the beam pattern functions of this polarization mode

This is called a null stream and, in the context of GR, it was introduced as a means of separating

false-alarm events due, say, to instrumental glitches from real detections [212*, 101*].

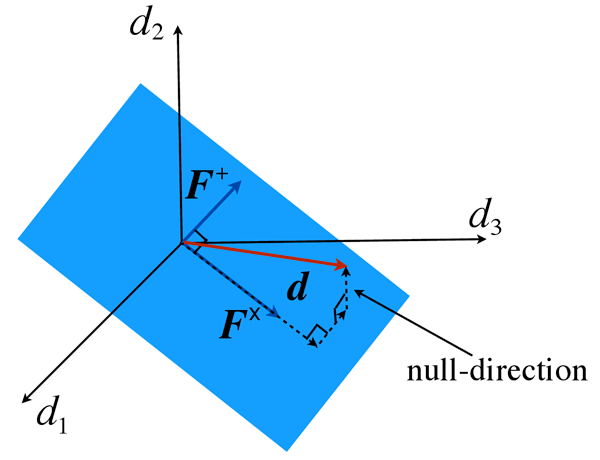

With just three independent detectors, we can choose to eliminate the two tensor modes (the plus and cross-polarizations) and construct a GR null stream: a linear combination of data streams that contains no signal consistent within GR, but could contain a signal in another gravitational theory, as illustrated in Figure 4*. With such a GR null stream, one can carry out null tests of GR and study whether such a stream contains any statistically-significant deviations from noise. Notice that this approach does not require a template; if one were parametrically constructed, such as in [102*], more powerful null tests could be applied. In the future, we expect several gravitational wave detectors to be online: the two aLIGO ones in the United States, Advanced VIRGO (adVirgo) in Italy, LIGO-India in India, and KAGRA in Japan. Given a gravitational-wave observation that is detected by all five detectors, one can then construct three GR null streams, each with power in a signal direction.

For pulsar timing experiments where one is dealing with data streams of about a few tens of pulsars, waveform reconstruction for all polarization states, as well as numerous null streams, can be constructed.

4.3 Stochastic background searches

Much work has been done on the response of ground-based interferometers to non-tensorial polarization modes, stochastic background detection prospects, and data analysis techniques [299, 323, 191, 329*, 121]. In the context of pulsar timing, the first work to deal with the detection of such backgrounds in the context of alternative theories of gravity is due to Lee et al. [284*], who used a coherence statistic approach to the detection of non-Einsteinian polarizations. They studied the number of pulsars required to detect the various extra polarization modes, and found that pulsar timing arrays are especially sensitive to the longitudinal mode. Alves and Tinto [22*] also found enhanced sensitivity to longitudinal and vector modes. Here we follow the work in [329*, 99*] that deals with the LIGO and pulsar timing cases using the optimal statistic, a cross-correlation that maximizes the SNR.

In the context of the optimal statistic, the derivations of the effect of extra polarization states for ground-based instruments and pulsar timing are very similar. We begin with the metric perturbation written in terms of a plane wave expansion, as in Eq. (50*). If we assume that the background is unpolarized, isotropic, and stationary, we have that

where is the gravitational-wave power spectrum for polarization

is the gravitational-wave power spectrum for polarization  .

.  is related to the

energy density in gravitational waves per logarithmic frequency interval for that polarization through

where

is related to the

energy density in gravitational waves per logarithmic frequency interval for that polarization through

where  is the closure density of the universe, and

is the energy density in gravitational waves for polarization

is the closure density of the universe, and

is the energy density in gravitational waves for polarization  . It follows from the plane wave expansion

in Eq. (51*), along with Eqs. (101*) and (102*) in Eq. (103*), that

and therefore

. It follows from the plane wave expansion

in Eq. (51*), along with Eqs. (101*) and (102*) in Eq. (103*), that

and therefore

For both ground-based interferometers and pulsar-timing experiments, an isotropic stochastic

background of gravitational waves appears in the data as correlated noise between measurements from

different instruments. The data set from the  instrument is of the form

instrument is of the form

corresponds to the gravitational-wave signal and

corresponds to the gravitational-wave signal and  to noise. The noise is

assumed in this case to be stationary and Gaussian, and uncorrelated between different detectors,

for

to noise. The noise is

assumed in this case to be stationary and Gaussian, and uncorrelated between different detectors,

for  .

.

Since the gravitational-wave signal is correlated, we can use cross-correlations to search for it. The cross-correlation statistic is defined as

where is a filter function to be determined. Henceforth, no summation is implied on the

detector indices

is a filter function to be determined. Henceforth, no summation is implied on the

detector indices  . At this stage it is not clear why

. At this stage it is not clear why  depends on the pair of data sets

being correlated. We will show how this comes about later. The optimal filter is determined by maximizing

the expected SNR

Here

depends on the pair of data sets

being correlated. We will show how this comes about later. The optimal filter is determined by maximizing

the expected SNR

Here  is the mean

is the mean  and

and  is the square root of the variance

is the square root of the variance  .

.

The expressions for the mean and variance of the cross-correlation statistic,  and

and  respectively,

take the same form for both pulsar timing and ground-based instruments. In the frequency domain,

Eq. (109*) becomes

respectively,

take the same form for both pulsar timing and ground-based instruments. In the frequency domain,

Eq. (109*) becomes

is then

where

is then

where  is the finite time approximation to the delta function,

is the finite time approximation to the delta function,  . With this in

hand, the mean of the cross-correlation statistic is

and the variance in the weak signal limit is

where the one-sided power spectra of the noise are defined by

in analogy to Eq. (76*), where

. With this in

hand, the mean of the cross-correlation statistic is

and the variance in the weak signal limit is

where the one-sided power spectra of the noise are defined by

in analogy to Eq. (76*), where  plays here the role of

plays here the role of  .

.

The mean and variance can be rewritten more compactly if we define a positive-definite inner product using the noise power spectra of the two data streams

again in analogy to the inner product in Eq. (78*), when considering inspirals. Using this definition where we recall that the capital Latin indices stand for the polarization content. From the

definition of the SNR and the Schwartz’s inequality, it follows that the optimal filter is given by

where

stand for the polarization content. From the

definition of the SNR and the Schwartz’s inequality, it follows that the optimal filter is given by

where  is an arbitrary normalization constant, normally chosen so that the mean of the statistic gives

the amplitude of the stochastic background.

is an arbitrary normalization constant, normally chosen so that the mean of the statistic gives

the amplitude of the stochastic background.

The differences in the optimal filter between interferometers and pulsars arise only from

differences in the overlap reduction functions,  . For ground-based instruments, the signal

data

. For ground-based instruments, the signal

data  are the strains given by Eq. (57*). The overlap reduction functions are then given by

are the strains given by Eq. (57*). The overlap reduction functions are then given by

and

and  are the locations of the two interferometers. The integrals in this case all have

solutions in terms of spherical Bessel functions [329*], which we do not summarize here for

brevity.

are the locations of the two interferometers. The integrals in this case all have

solutions in terms of spherical Bessel functions [329*], which we do not summarize here for

brevity.

For pulsar timing arrays, the signal data  are the redshifts

are the redshifts  , given by Eq. (63*). The overlap

reduction functions are then given by

, given by Eq. (63*). The overlap

reduction functions are then given by

and

and  are the distances to the two pulsars. For all transverse modes pulsar timing

experiments are in a regime where the exponential factors in Eq. (121*) can be neglected [30, 99*], and the

overlap reduction functions effectively become frequency independent. For the

are the distances to the two pulsars. For all transverse modes pulsar timing

experiments are in a regime where the exponential factors in Eq. (121*) can be neglected [30, 99*], and the

overlap reduction functions effectively become frequency independent. For the  and

and  mode the

overlap reduction function becomes

where

mode the

overlap reduction function becomes

where  is the angle between the two pulsars. This quantity is proportional to the

Hellings and Downs curve [231]. For the breathing mode, the overlap reduction function takes the closed

form expression [284*]:

For the vector and longitudinal modes the overlap reduction functions remain frequency dependent and

there are no general analytic solutions.

is the angle between the two pulsars. This quantity is proportional to the

Hellings and Downs curve [231]. For the breathing mode, the overlap reduction function takes the closed

form expression [284*]:

For the vector and longitudinal modes the overlap reduction functions remain frequency dependent and

there are no general analytic solutions.

The result for the combination of cross-correlation pairs to form an optimal network statistic is also the same in both ground-based interferometer and pulsar timing cases: a sum of the cross-correlations of all detector pairs weighted by their variances. The detector network optimal statistic is,

where is a sum over all detector pairs.

is a sum over all detector pairs.

In order to perform a search for a given polarization mode one first needs to compute the overlap

reduction functions (using either Eq. (120*) or (121*)) for that mode. With that in hand and a form for the

stochastic background spectrum  , one can construct optimal filters for all pairs in the detector

network using Eq. (119*), and perform the cross-correlations using either Eq. (109*) (or equivalently

Eq. (111*)). Finally, we can calculate the overall network statistic Eq. (124*), by first finding the variances

using Eq. (114*).

, one can construct optimal filters for all pairs in the detector

network using Eq. (119*), and perform the cross-correlations using either Eq. (109*) (or equivalently

Eq. (111*)). Finally, we can calculate the overall network statistic Eq. (124*), by first finding the variances

using Eq. (114*).

It is important to point out that the procedure outlined above is straightforward for ground-based interferometers. However, pulsar timing data are irregularly sampled, and have a pulsar-timing model subtracted out. This needs to be accounted for, and generally, a time-domain approach is more appropriate for these data sets. The procedure is similar to what we have outlined above, but power spectra and gravitational-wave spectra in the frequency domain need to be replaced by auto-covariance and cross-covariance matrices in the time domain that account for the model fitting (for an example of how to do this see [162]).

Interestingly, Nishizawa et al. [329*] show that with three spatially-separated detectors the tensor,

vector, and scalar contributions to the energy density in gravitational waves can be measured

independently. Lee et al. [284] and Alves and Tinto [22] showed that pulsar timing experiments are

especially sensitive to the longitudinal mode, and to a lesser extent the vector modes. Chamberlin and

Siemens [99] showed that the sensitivity of the cross-correlation to the longitudinal mode using

nearby pulsar pairs can be enhanced significantly compared to that of the transverse modes. For

example, for the NANOGrav pulsar timing array, two pulsar pairs separated by  result in

an enhancement of 4 orders of magnitude in sensitivity to the longitudinal mode relative to

the transverse modes. The main contribution to this effect is due to gravitational waves that

are coming from roughly the same direction as the pulses from the pulsars. In this case, the

induced redshift for any gravitational-wave polarization mode is proportional to

result in

an enhancement of 4 orders of magnitude in sensitivity to the longitudinal mode relative to

the transverse modes. The main contribution to this effect is due to gravitational waves that

are coming from roughly the same direction as the pulses from the pulsars. In this case, the

induced redshift for any gravitational-wave polarization mode is proportional to  , the

product of the gravitational-wave frequency and the distance to the pulsar, which can be large.

When the gravitational waves and the pulse direction are exactly parallel, the redshift for the

transverse and vector modes vanishes, but it is proportional to

, the

product of the gravitational-wave frequency and the distance to the pulsar, which can be large.

When the gravitational waves and the pulse direction are exactly parallel, the redshift for the

transverse and vector modes vanishes, but it is proportional to  for the scalar-longitudinal

mode.

for the scalar-longitudinal

mode.

Lee et al. [285] studied the detectability of massive gravitons in pulsar timing arrays through stochastic

background searches. They introduced a modification to Eq. (59*) to account for graviton dispersion, and

found the modified overlap reduction functions (i.e., modifications to the Hellings–Downs curves Eq. (122*))

for various values of the graviton mass. They conclude that a large number of stable pulsars ( ) are

required to distinguish between the massive and massless cases, and that future pulsar timing experiments

could be sensitive to graviton masses of about

) are

required to distinguish between the massive and massless cases, and that future pulsar timing experiments

could be sensitive to graviton masses of about  (

( ). This method is competitive with

some of the compact binary tests described later in Section 5.3.1 (see Table 2). In addition, since the

method of Lee et al. [285] only depends on the form of the overlap reduction functions, it is

advantageous in that it does not involve matched filtering (and therefore prior knowledge of

the waveforms), and generally makes few assumptions about the gravitational-wave source

properties.

). This method is competitive with

some of the compact binary tests described later in Section 5.3.1 (see Table 2). In addition, since the

method of Lee et al. [285] only depends on the form of the overlap reduction functions, it is

advantageous in that it does not involve matched filtering (and therefore prior knowledge of

the waveforms), and generally makes few assumptions about the gravitational-wave source

properties.

![⌊ ⌋ F +F × F x F y Fb F ℓ | 1+ 1× 1x 1y 1b 1ℓ| [ F + F × F x F y F b F ℓ] ≡ || F2. F 2. F.2 F2. F.2 F.2|| . (92 ) ⌈ .. .. .. .. .. .. ⌉ F +F × F x F yF b F ℓ D D D D D D](article561x.gif)

![1 [ 1 ] P(d |h ) = ----D∕2-exp − -|d − F h |2 . (93 ) (2π) 2](article566x.gif)

![[ ] L ≡ ln P-(d-|h)-= 1- |d|2 − |d − F h |2 . (94 ) P (d|0) 2](article567x.gif)

orthogonal to the GR subspace

spanned by

orthogonal to the GR subspace

spanned by  and

and  , along with a perpendicular subspace, for 3 detectors to build the GR

null stream.

, along with a perpendicular subspace, for 3 detectors to build the GR

null stream.

![{ [ ( ) ]} + 1 1 − cosξab 1 − cosξab 1 Γab = 3 --+ ---------- ln ---------- − -- , (122 ) 3 2 2 6](article635x.gif)